(SPOILERS) Music for the Royal Fireworks: Composing a Puzzle

If you’ve read my post about writing the 2024 MIT Mystery Hunt, you might already know that I had a puzzle left on the cutting room floor.

Well, here it is: a composition for piano six hands1 that also functions as a five-part minimeta.

Naturally, if you want to try it out, or you want the challenge of “identify as many pieces as possible”, you should probably refrain from reading this until you have—it’s a pretty deep dive into the construction process.

So, how did this come to be?

Overture

If you’ve read any of my previous recaps, you may have noticed that every title and heading has something to do with classical (…sorry, Western art) music. Not without reason—it’s by far the genre I listen the most to. Something about its aesthetic just appeals to me—even the other things I listen to regularly are generally orchestral in nature (or have an odd time signature, which is practically guaranteed to attract my attention).

The fact that it was also the one I had the most exposure to (from quiz bowl) also helped, as did the typical experience of learning plural instruments in elementary. But those weren’t really formative—at the time I typically left the music questions to the humanities mains on my team, and while I did the typical music theory nerd things of learning about intervals and figured bass and whatnot I mostly used the instruments to play things I liked, which back then was just Paradox Interactive soundtracks and national anthems.

This changed some time around the transition to high school, when I found a Classical Music Mashup on a cursory browse of YouTube during an otherwise quiet school day.

I don’t know what about it appealed to me. Maybe it was the knowledge gateway it represented. Maybe it was hearing the few that I recognized incorporated seamlessly into a larger piece. Maybe it was the humorous stylistic choice of using composer heads as the notes. Whatever the case, I loved the work.

If you asked 9th grade Adalbert what his favorite work of music2 was, the answer would, far and away, be Dvořák’s 9th Symphony (AKA the New World Symphony), mostly because it was a pretty common subject for middle school quiz bowl tossups. Eventually I’d extend my listening reach, taking suggestions from other compilations of classical music, a habit that would even contribute score on a quizbowl tossup or two3. Occasionally I’d be reminded that the Mashups existed, and be pleasantly surprised to see a third or fourth added to their ranks. The fourth was my war song for much of my sophomore year in college.

I’ve also always felt that classical music is… let’s say “underrepresented” in the puzzling world. Always overshadowed by its more popular counterparts, with their easily-researchable songs and canonical titles and organizational structure and rambles off into unintelligibility

But yeah, besides one UMD Puzzle and a brief mention at the end of Dancing Triangles in 2022 (that I also failed to recognize despite Mashup III), classical hasn’t really gotten a lot of press in puzzlehunt history that I know of.

So let’s give it some.

Bourrée

Point being, I’ve always wanted to get the classical canon into a puzzle… although my initial ideas on that front were pretty basic, and mostly of the “encode an English answer in X format in the baseline and clue it with Y piece of music” form.

Yet the first time I thought to write the puzzle was in late July, having had the impulse to listen to the mashups again. Since this was capital-H Hunt, though, I aspired for something grander. Perhaps lightly inspired by the recently-late Jack Lance and his thoughts on puzzle structure, I chose to make the answers to each a musical quotation, and indeed to conduct the entire solving process entirely within the musical domain. (Or as much as possible, anyway.) This would be my attempt at innovation.

I picked as thematic an answer as I could muster from the pool and essentially built the puzzle structure around it.4

I carried forward one idea from my old plan (the Gershwin, since New York Point doubled as a musical encoding) and hammered out another three ideas (what would become the first three movements). I had a fifth in reserve, but I always had apprehensions on if I could ever make it work, so I spent time between composition to find inspiration.

At the same time, I started selecting phrases from the mashups to reference—a process which, given my extraction method, turned out to be much more constrained than I realized. Not only did it have to extract the right letters, but the phrase I chose had to identify a specific segment uniquely, and it had to be able to be encoded with my chosen methods. Fortunately, it worked out well enough: two works that stuck to the major scale to give to the less flexible methods, a fairly-arbitrary method I could assign to works with accidentals, and one work that… was just a repeated sequence of one note, so the Gershwin had to take it as the only method that could encode lengths. I just needed to devise another method that could accept an arbitrary melody.

The constraint this process imposed, though, got me worried about whether a fifth mashup would come out at the 11th hour, so I also chose to do some research to be safe on that front.

And this is how I learned that Grant Woolard left the world a few months after publishing CMM IV.

…

……

Guess I was writing two memorial puzzles for this hunt.

I decided pretty early on that the work would be structured much like Pictures at an Exhibition: a variation on a “promenade” theme (which also contained the meta) before each movement. I had recently gotten into Elgar’s Enigma Variations, and I figured that they would be perfect for the role.

I got the vibe of Section A down really quickly—light melodies playing over one theme, relatively linear, lightly inspired by Mingchi and CMM I’s own Unfinished Symphony section (hence it ending on Boccherini’s famous Minuet). However, the extraction method made it necessary to cut off every melody at the last note—incredibly jarring, and very hard to make blend into the rest of the music.

For Promenade B, of course, I wanted Nimrod to take center stage, and transition directly into another slow piece, before immediately picking up speed.

Section B’s layout was more in the vein of Grant himself, since by nature I was always going to be playing two pieces at a time (bar the Mahler at the beginning). I mapped out every piece I could find that I knew was named after a European location, and wound up using nearly all of them to form the symbols. It also happened to be that I could chunk the scale to divide the melody cleanly into major and minor sections, so I only needed seven shapes total—one for each step in the scale.

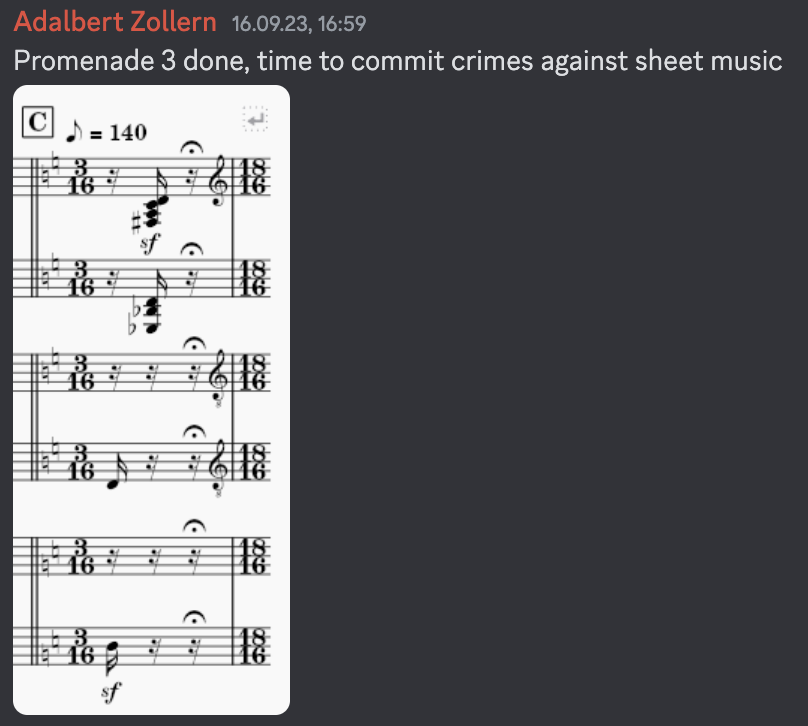

I had half of it done by the time I had to fly back to MIT, futzed around a bit on finding a good part of Finlandia to arrange against a piece in major, and eventually had this done in September. The process got me hooked on the Scottish Symphony in the meantime.

Now I had reached the part I was dreading. No, not Section C—I had enough of a plan for that—but the promenade before it.

Elgar, as a bit of a joke, made Variation II extremely chromatic. Which made it extremely hard to arrange against anything else. And as far as I could tell, this was nearly impossible to avoid.

Fortunately, this segment was a short 7 measures, and I could immediately follow it up with Rite of Spring. Which essentially made this part of the work the chaos movement.

Section C I knew I wanted to be extremely bombastic: very loud with a lot of massed chords, to fit the tone of Rite of Spring (though without delving into its extreme dissonance). The way I had originally planned it out I may have been forced to use some extremely wacky pieces to encode 1s or 7s, but the Vivaldi I chose for it thankfully avoided moving under 3 or over 5. Which meant I could just take the most famous 5 (Mars by Holst, which I wanted in anyways) and use the rest of the space on introducing more composers, like Vivaldi or Prokofiev.

I couldn’t find enough 3s that fit the tone, though, so I compromised slightly by using a 6/8 (Schubert’s Death and the Maiden String Quartet) and modifying the cluephrase. In the end, the cluephrase allotted just enough space to put it all in, all by the end of September. (My favorite part of the section is almost certainly the 5/4 cross-rhythm at the end.)

But now I reached the real roadblock: I still hadn’t found an idea I was satisfied with for Section D.

I waffled on this for a bit; I was planning Modern Architecture around the same time, not to mention it was midterm season. But even after I completed the fourth Promenade section I still wasn’t completely happy with it.

I knew I wanted Well-Tempered Clavier, and to have “well-tempered” hint at intervals and transposition. Eventually I chose to focus the other pieces on the “Clavier” part, rather than risk people attempting to identify pieces more obscure than the preludes I had chosen.

Hence, Romantic-sounding piano music. (I had, by this point, noticed that some prominent piano composers of the era—Debussy, Rachmaninoff, and Schumann—hadn’t made it in yet, which made it more tempting to lean into it.) As such, the composition begins to lean into an expressive angle. You might have noticed the rubato marking on the Rachmaninoff; I put a bunch of hidden tempo markings to simulate it.

I then spent a while picking the precise parts of WTC to use, because—again—I had chosen an ordering and extraction method that was extremely constraining on my piece choices. Minor keys were out straight out the gate, and they had to be in a precise final ordering that worked well with the other more famous pieces.

I did find something that worked well. Then I chose to put aesthetically-similar pieces next to each other to add to the impact, which breaks the standard puzzle convention for initial ordering that doesn’t actually exist in this space.

Conveniently, this put the Sonata Pathétique at the end. And I already knew it counterpointed well with the Enigma—thus an attacca5 transition directly into Promenade 5, which let it stand in for the unused Lacrimosa in the section. The non-melody parts were changed slightly to give it the character of the last movement of Pictures at an Exhibition.

At that point, I was relieved to be done with the most taxing part of the work, and quickly capped it off with Section E—a short codetta. Just in time for the fall break.

La Paix

I already knew classical was hard to identify—the aforementioned Dancing Triangles was actually the first thing to introduce me to Musipedia as a concept, and I still couldn’t really get it to work reliably at the time. So to prepare for the inevitable, I instead put programming effort into a mechanism that would check if a piece was in the work.

I also knew off the bat that we really only had so many people who might have had a shot at this identification without the tool. No pressure.

The first testsolve, as expected, went turbulently. Clearly I didn’t clue the mechanisms aggressively enough.

The band-aid fix for this was to add a lot of clutter to the endcard: staves providing “enumerations” (length markers) for the answer pieces and further blue annotations indicating the mechanic (plus a lot of tweaking for that).

I was never happy with the fix. It did, however, prove helpful for the testsolvers. I tweaked it several times over the course of the testsolve, which got through with its help… after a whole fortnight and change. Whew.

A few more tweaks and it was ready for a second testsolve, which then… proceeded to drag for another fortnight.

You know the rest of the story—it gets axed near the start of winter break, an emergency puzzle is pasted in its place, I slip mentally for a few days and then bang out Transcendental Algebra in a significantly shorter timeframe, all of hunt happens.

Melody Medley was basically the embodiment of risk factors for puzzle death.

- Innovation in puzzlehunts already sets a higher bar on difficulty. Melodies are inherently messier than English (cf. Schönberg), so it’s harder to confirm you have the right things, especially if your melody is incomplete. There’s no Nutrimatic to help you, just intuition.

- Its topic, being quite rare, meant I really couldn’t seek help on construction if I wanted it to actually have testsolvers. We had like two classical musicians on the team, which is already a lot. Not to mention that knowledge is impossible to control for—I already tried to set up potential alternate methods of identifying the music (or avoiding identifying the music, if you know what you’re doing).

- Its bulk and already-high construction difficulty made it difficult to pivot onto another answer when its round already had several difficult puzzles. This was the straw that broke the metaphorical camel—I had essentially built its structure around one suitable answer.

In other words, I aimed for the sun and got my wings burnt for the trouble.

Of course, I knew the risk quite well. Didn’t stop me from lying despondently in bed straight through Christmas. But so it is with major investments of time and effort.

La Réjouissance

I always planned to rework the puzzle for the epilogue. The reality, though, is that I never found the time or motivation to recompose everything from scratch.

I did get some basic ideas down—the plan was to rework the puzzle into a full round (since this was essentially a round-length puzzle, just like Ripple Effect). I even came up with a meta answer, though using it for this hunt would likely have run into some problems (exercise left to the reader), and answers to go with it (which unfortunately were even more constrained and also didn’t exactly mesh well with my extraction methods).

Eventually, as 2024 bled into 2025, and the rest of the Epilogue was being hammered out6, we settled on releasing it as is. However, over time I had become somewhat unhappy with the puzzle’s then-current state. The coda really was just tacked on at the time; I rewrote it to call back to Medley IV, where it leads directly off the Pathetique at the end (and even added the other pieces in its section to strengthen the connection). I also rewrote a few of the melodies for easier identification.

Slightly more controversially, I also took the opportunity to write the crutches out of the puzzle. So the endcard was replaced with a simpler one (just two credits lines on a white background) and its clues scattered across the sheet music. The flavortext, formerly needing the length of a paragraph to justify the existence of a melody checker, was now just one line of description and one line of clarification taken from the endcard. The major crutches needed to justify using the Solresol symbols were now three articulation markers on the extant G-D-G, Sudre’s “initials”7 as an annotation, and CPE Bach’s Solfeggietto to encourage reading the spare notes as solfège. Section E’s chords now had to be a shorter message, so I used Grade 2 Braille, just to push future Braille usage in puzzles in that direction (Grade 1’s not actually commonly used, per Sara, and admittedly its usage in puzzles has become a bit bland).

The puzzle hadn’t looked this clean in ages. The one major loss was the enumerations, but I was OK with removing them because actually identifying the answers wasn’t necessary to the solve path. Also because enumerations in the musical space can introduce cheese in a way that doesn’t apply to English.

There were concerns from the rest of the editorial team—in particular, that identification would be Too Hard without having some way of checking the work. In the end, I chose not to add the checker back in.

I had planned for an early sleep the Saturday the hunt was set to release, as I had something out of town that I needed to wake up early for. Which made it annoying when one of the other editors went behind my back to add the entire list of used pieces to the puzzle as I was going to bed, and I had to spend half an hour to get them to not.

So why did I do this? Well, artistic intent.

Menuets

Grant’s mashup videos always came with a challenge at the bottom: identify as many of the dozens of pieces he incorporated into the work as possible. It was essentially a puzzle by a classical musician, for classical musicians.

In the end, I wanted the presentation and the initial experience to reflect a Grant Woolard video as closely as I could (without making the reference too obvious, so no composer heads). And a lot of the bells and whistles that would ostensibly make for a smoother solve experience really got in the way of that more than anything. Adding a list, or even suggesting that such a list would be provided at the cost of sending a hint that would be refunded (as the editor in question suggested later), would tear the soul out of the puzzle.

It was probably for the best that this puzzle wasn’t in Mystery Hunt in its original location. Not for the reason everyone wants to hear, but because everything needed to make it “accessible to a wider audience” would have undermined the intent. Once it was made a side-quest, I felt a lot more comfortable with removing them.

Which sort of ties back into why popular music gets all the billing for music ID in puzzlehunts: because it’s accessible. Accessible because they have lyrics unearthable by a single Google search. Accessibility facilitated by apps like AHA Music and Shazam, which gives them all the flexibility with their music choices. Want to use the most obscure song on the most obscure album because it fits well in your puzzle? As long as it’s in there, the tools will pick it up!

It’s a bit of a vicious cycle. Writers will use more obscure popular music because they know solvers will use an app for it. Eventually The App just becomes a must-have in the solver’s toolkit. Other writers will know that solvers are going to use The App, and attempt to write puzzles that are completely opaque to it. The standard puzzlehunting arms race resulting from automation, and one that’s prone to making some extremely divisive puzzles, since designing puzzles to beat the app also risks making them opaque to humans. Even humans that know your dataset well.

In a way, I’m kind of glad that classical hasn’t gotten this treatment. Sure, Musipedia exists, but using it is still sufficiently non-trivial and prone to inaccuracies that you’re encouraged to make a manual first pass. The puzzles in Medley are all relatively simple mechanically (once you’re past the initial hurdle of identification). You really just need someone who can identify8. Just like the old hunts, or at least how I’m told the old hunts went.

-

Ignore the several voice crossings that would be completely unrealistic to play in actual six hands. ↩

-

Obviously, most of the time people would substitute this phrasing for “song”. ↩

-

I think this was at a rerun of NASAT. More precisely, it was about Mars, the Bringer of War, but the clue was about the horn melody from the following Venus movement. ↩

-

I realized several months too late that I could have done something funny with the answer extraction; if you’ve finished the puzzle you’d’ve seen me use the trick already. Exercise left to the reader. ↩

-

Normally there’s a pause between movements of a work. Attacca indicates to skip that pause. ↩

-

Pun intended. ↩

-

Written FSud so as not to be confused with Franz Schubert. Except it’s also apparently readily decipherable with Nutrimatic, not that I consider this a drawback. ↩

-

Doesn’t even have to be someone who knows the canon. There’s many ways to discover a piece: the top listing on the composer’s Wikipedia page, Grant’s mashups, or just the puzzle’s own constraints (Section B comes to mind). ↩